Have you ever had the experience where a visual scene reflected your inner state? This is called equivalence. In this post, we’ll explore the idea of equivalence and its history in photography.

But first, a Little Photographic History

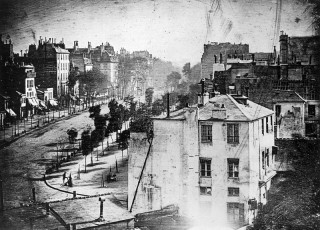

* Thomas Wedgewood was a pioneer in the development of photography and is credited with creating the first photograph in 1790. Over the next century, technology evolved and photography was thought of mostly as a way to record or document an image.

The f/64 group was formed in the 1920’s and emphasized straight photography – sharply focused photographs of natural forms. Members included Imogen Cunningham, Ansel Adams, and Edward Weston. They were opposed to Pictorialism, a style of photography that became popular in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Photographs were manipulated (through blur or adding colour or brush strokes) to create an emotional intent. Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Steichen were masters of this style.

Stieglitz’s Clouds

Alfred Stieglitz introduced the idea of equivalence in photography through his cloud series, the first intentionally produced abstract photographs. This was a movement away from a strictly literal interpretation. You can read about how this project came about here. He photographed clouds from 1922 – 1935.

“A symbolist aesthetic underlies these images, which became increasingly abstract equivalents of his own experiences, thoughts, and emotions. The theory of equivalence had been the subject of much discussion at Gallery 291 during the teens, and it was infused by Kandinsky’s ideas, especially the belief that colors, shapes, and lines reflect the inner, often emotive “vibrations of the soul.” In his cloud photographs, which he termed Equivalents, Stieglitz emphasized pure abstraction, adhering to the modern ideas of equivalence, holding that abstract forms, lines, and colors could represent corresponding inner states, emotions and ideas.” ~ The Phillips Collection

Photography as Self-Expression

Photographer Minor White spoke of levels of equivalence.

1. The photograph itself – the visual foundation of the visual experience.

2. The viewer’s response – how the photograph resonates.

3. The remembered image – the inner experience after the photograph is no longer in sight.

Do we love it or dislike it intensely? Has it made us realize something about ourselves? Has it changed us in some way? A photograph that is an equivalent touches something deep inside of us. It serves as a symbol, an outward sign of what’s inside. It expresses a feeling, not so much a feeling about the subject rather a feeling inside the photographer for which the subject is a metaphor.

To me, this describes photography as a form of self-expression. The camera looks both ways. The photograph always mirrors the photographer in some way.

Contemplative Photography

From my understanding of Miksang contemplative photography (which stems from Buddhist thought), images are based on careful observation and presence. They reflect the state of mind of the photographer in that moment, a mind which is clear and unfiltered. The photograph is what the photographer sees pre-thought, before judgments or concepts materialize.

In the mid-20th century, Chogyam Trunpa Rinpoche “began to explore ways the camera could be used to create images of the world of form: the naked appearance of things, before they are overlaid with any conceptions about what they mean or what they are.” (Seeing Fresh)

The emphasis is on showing what is, without judgment. If there is an expression of feeling, it is one that is formed by the connection. I’m not sure if any mind can be truly unfiltered, however I do believe that we can train ourselves to become more aware of our filters.

“The state of mind of a photographer while creating is a blank…For those who would equate “blank” with a kind of static emptiness, I must explain that this is a special kind of blank. It is a very active state of mind really, a very receptive state of mind, ready at an instant to grasp an image, yet with no image pre-formed in it at any time. We should note that the lack of a pre-formed pattern or preconceived idea of how anything ought to look is essential to this blank condition. Such a state of mind is not unlike a sheet of film itself – seemingly inert, yet so sensitive that a fraction of a second’s exposure conceives a life in it. (Not just life, but “a” life).” -Minor White, The Camera Mind and Eye

This is a wonderful expression of contemplative photography and an evolution of the concept of equivalence. Nothing is planned. It’s about engagement, encounter, and reciprocity. The photographer is open to what comes. In this article, Found Photographs, Minor White describes this process through the experience of a broken bowl.

The Christian monk, Thomas Merton, was a contemporary of Rinpoche, and also a photographer. He saw photography as a connection with the divine or spirit.

“Merton called his camera a Zen camera. The Japanese term “yugen” means to form a still point of oceanic, calm and penetrating insight. D.T. Suzuki, Merton’s Zen mentor says, “All great works of art embody in them yugen whereby we attain a glimpse of things eternal in the world of constant changes.” Merton’s photography was imbued with yugen, offering us gimpses of a world less forlorn, one fraught with divine vestiges, if we would only make the effort to convert our eyes to pay attention and look!” ~ Thomas Merton, Master of Attention by Robert Waldron

John Daido Loori was a student of Minor White. In his book, The Zen of Creativity, he shares many stories of how White influenced his thinking on photography. I was particularly struck by his thoughts on intimacy.

“Intimacy is the place where opposites merge.”

There is no subject, no object, no viewer – everything is merged (one) and all are changed.

I really love this idea. To me, that’s what photography is all about, an intimate moment of connection where subject and photographer meet and both are changed. The photograph is the result of the connection.

Here is a photograph that changed me. Freeman Patterson’s image that graces the cover of his biography, Shadowlight. It was taken in an abandoned mining town in South Africa. It touched something deep inside of me – the open door, the three rectangles of light (very much a Christian metaphor for me at the time), the shapes, the theme of change. It still touches me every day as it hangs in my living room.

How has a photograph changed you?

Note: You can find many of the books cited here in my Amazon store on photography.

** Books mentioned have Amazon affiliate links, meaning I make a few cents if you purchase through my link. I only recommend books that I’ve read.

Thank you for this post, I have found it most interesting. I have not looked at all the links but will come back, I got sidetracked by Alfred Stieglitz documentary link The Eloquent Eye, I was fascinated!

It is Interesting to look back and see the progression of photography.