For the Contemplative Photographer, the camera is viewed as an extension of a person’s heart and mind and the resulting photographs as a visual, and highly personal diary of experience and expression. ~ Patricia Turner

I was thrilled to meet Patricia Turner at my contemplative photography retreat at Bethany Spring in Kentucky. She is the author of the blog, A Photographic Sage, where she writes about contemplative photography from a Taoist perspective.

Patricia just happened to be on a three week pilgrimage of sites related to the Trappist monk, Thomas Merton, one of my mentors in contemplative living. During the retreat, she was able to visit Merton’s hermitage at the Abbey of Gethsemani, and wrote about the experience here.

A delightful person and very knowledgeable and passionate about contemplative photography, Patricia is also a retired school teacher of art and travels extensively. During that weekend, I learned that she had published a small book called A Field Guide for the Contemplative Photographer, now available as a free e-book. It is a fabulous piece of work and this interview is based on questions related to the book. You can download the book as a pdf file at the end of this post.

First, please tell us a little about you, your background, and how you “found” contemplative photography.

I think I would say that it was contemplative photography that found me! I had gone to the Outer Hebrides in 2005 on a grant to photograph in the footsteps of Paul Strand’s visit in 1954. An image I had made of two horses seemed to click with a poem in the Carmina Gadelica, a book of ancient Gaelic prayers from the Western Isles that I had taken with me. The horses, which were looking in opposite directions seemed to mirror the opening phrase of the prayer, “As it was, As it is, As it shall be evermore…” It was the first moment that I realized that images could be more than just a document of something seen but a reflection of a thought or feeling.

Here’s a link to the blog post where I discuss this.

As an aside, I majored in photography and film making in the late 1970’s and spent the next 30+ years teaching art in a public school system outside of Boston.

You begin the field guide with suggestions for equipping the body and mind. What would you say are the most important ingredients?

I would say a journal and an empty bowl. Being a student of Taoist philosophy, the latter is the essential starting point for me. When one is able to clear the mind completely and be totally open to whatever one may come across in the landscape, without preconceptions and without judgment, then one is more capable of receiving the wisdom of the world around them. My classically trained photographic mind often interfered in the early days. The journal is necessary for recording the fleeting impressions, in words or sketches, that are more authentic, more valuable that those recorded in “hindsight”.

Here’s a post on the “empty bowl.”

Please explain what you mean by “shunpiking.” Where did this word come from? Can you give us an example from your experience?

Shunpiking is a very old Yankee term for avoiding the well-traveled roads. Turnpike is an old English word for a major road between two towns. It is the way I like to travel … I’m forever veering off the main roads to explore the less traveled roads. I’ve found some amazing places that way.

Here is a post where I discuss “shunpiking” as a perfect way to practice the Taoist method of Wu Wei, or going with the flow!

Tell us a little about your process once you approach a landscape. I’m especially intrigued by your sketching the landscape first. One of my mentors, Fredrick Franck (author of The Zen of Seeing) felt that you could only really tap into the essence of something by drawing it. He was not a fan of photography. How does sketching the landscape prepare you for the photograph?

I spend a great deal of time just sitting and doing my “visual listening” exercises which may mean a guided meditation based on a poem or passage from a book or it may mean journaling my thoughts, creating “word trains” and sketching. Sketching forces me to slow down and really behold the landscape in front of me … it is way too easy to “click and run”… drawing takes time. It allows me to delineate the essential elements of line and shape and shade and I write all over it. Drawing draws my attention to things I may overlook without it.

I write about things I want to remember about the place. Later, after I make a “rough draft” of the image, I refer to my annotated sketch as a reference. I also use a viewfinder, a simple cardboard cutout that artists use for composing, to try out various ideas. Then I will make photographic sketches and spend time looking at them. Does the landscape ask me to move closer or further away?

I can spend an hour or more in one place … sometimes I return again and again because for me, photography is a creative endeavor between myself and the landscape. I try to give the landscape plenty of time to inform my images.

To me, contemplative photography is about the connection – the relationship. This seems to fit with the idea that images can be metaphors for the inner landscape. Can you give us an example (an image) where this has been true for you?

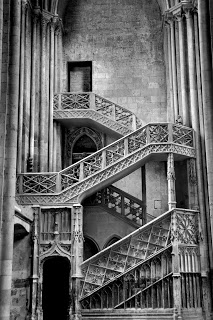

It was John O’Donohue who got me to see this most clearly. I can wax almost metaphysically about the idea that we receive the images that we are meant to receive! Metaphors are simply ways to shape our thoughts and the ones that speak the strongest to me I call “Icons of the Experience” and I read them just as you would a stained glass window or a text.

Here is a link to my practice of PhotoLectio.

It’s very hard to choose one image to cite but I’ll offer the one I will use in an upcoming post on Metaphor. It is my image of the staircase in Rouen Cathedral which I photographed last summer.

What is it that you love most about contemplative photography?

As someone who writes incessantly (I’ve kept a daily journal for 40 years), I love how contemplative photography gives me artifacts of experience … something to sit with and reflect on slowly, over time. It stimulates my writing in new and unexpected ways.

It seems the longer I practice contemplative photography, the fewer images I need to make to be happily engaged with the experience. The more attentive I become of the simple and insignificant, the sacred in the ordinary, the more I understand William Blake’s words, “Everything that is, Is Holy.”

Thank you, Patricia, for the e-book and for writing about contemplative photography and sharing your thoughts with us today.

Download Patricia’s Field Guide for Contemplative Photographers right here.

And, be sure to visit her wonderful blog, A Photographic Sage.

Thank you so much for this post, Kim. It is a real gift to be introduced to Patricia, her site, her approach, her work. I can’t wait to delve into her e-book. There is so much to take in here.

Thanks, Sherry. Wait until you see her site!

Kim,

I wanted to express my thanks for the fabulous newsletter you send me each week.

I am somewhat following along with Rilke, and love all the new connections you send my way. I barely have time to get the photos taken right now! I appreciate the effort you put in and the connections you send me. THanks!

You’re welcome! And thank you for taking the time to let me know. It means a lot.

Hi Kim!

Thank you so much for sharing the information about Patricia. I definitely want to read more about her and her philosophy.

I tried to download the ebook, and it said the file was damaged.

I’m sorry you had trouble downloading it, Gina. I don’t see a problem with it but will send you a copy by email.