Seeing is forgetting (or letting go of) our pre-conceptions, taking off labels, and cultivating beginner’s mind.

While studying the photography and writing of Uta Barth (a photographer of perception), I learned of the book, Seeing is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees (paid link) by Lawrence Weschler, about the artist, Robert Irwin. This book was the most influential for her so I decided it was time for me to read it. Doing so has been the highlight of my January. Below you’ll find a summary of the key points I took from the book. There are links to examples of Irwin’s work.

Background

Robert Irwin, who turns 90 this year, is considered one of the top 10 living artists in the U.S. today. He was a leader in the light and space movement, which began in Southern California back in the 60’s, yet few know who he is due to the unique nature of his work – making the viewer aware of their own perceptions and the richness available in every moment. How did he come to this? The book jacket says that “one day he got hooked on his own curiosity and decided to live it.”

This book is a memoir of sorts, as Irwin recounts his life through the conversations he had with Weschler, a cultural and political writer. We learn about Irwin’s childhood in Los Angeles (it was a good one) and his evolving thoughts about art and seeing. Over the course of the book, we get a picture of the stages Irwin went through in his art, beginning with painting evocative landscapes, moving to abstract expressionism, and then slowly doing away with the artist’s tools – figure, lines, and shapes – towards minimalism, his point zero.

Lines

Irwin’s questions, not the answers, always led him to the next stage. He used boredom as a means of discovery.

“Boredom is a very good tool. Because whenever you play creative games, you normally bring to the situation all your aspirations, assumptions, ambitions – all your stuff. And then you pile it all onto the painting, everything you want it to be. Boredom breaks that. You do the same thing over and over until you’re bored with it. Then all your Illusions, aspirations, just drains off. Now what you see is what you get, in all its threadbare reality, its lack of structure, its lack of meaning.”

After painting abstract pieces, Irwin began to focus on stripping away superfluous gestures to get to the necessary gesture. He wanted a visual vocabulary which would focus on presence. So, he began to experiment with lines in space. He spent hours painting lines in different places on the canvas, using his intuition as a guide. It was all a process of discovery. The finished canvases were incidental.

“Renaissance man tells the world what he finds interesting and tries to control it. I took to waiting for the world to tell me so I could respond. Intuition replaced logic.”

Dots

Irwin’s next question was about how to paint a painting without a line, yet without it becoming a void. He began to experiment with dots, which created patterns which were felt as vibrations. What Irwin was trying to get across with the dot paintings is that the medium is not the message; that the value of art is not in the painting itself, but in what happens to the viewer.

Irwin describes three stages of teaching. First, establish a performance level, i.e. develop their confidence technically. Second, place them in an historical context. Who came before them and what questions were they tackling? What questions are being asked today? And finally, what does the student have to contribute within this context? At this point, they begin to assign themselves their own tasks.

“Once you’ve learned how to make your own assignments, then you’ve learned the only thing you really need to get out of school, you’ve learned how to learn. You’ve become your own teacher.”

Discs

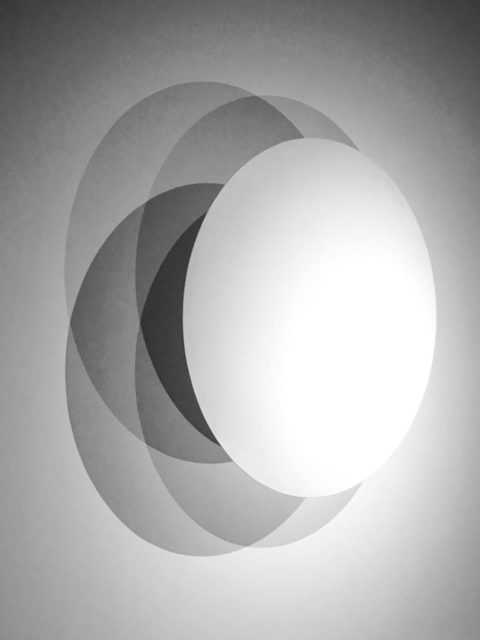

Robert Irwin Disc, Albright Knox Gallery

The dots achieved their purpose in creating a perceptual energy. Yet, the experience was still confined to a frame. This led to his next question – why does a painting exist within a frame? He wondered how he could paint a painting that doesn’t begin and end at the edge, but starts to take in and become involved with the space or environment around it? This made him think about two elements that he’d previously considered distractions – the lighting and the wall. His next project revolved around discs. For months, he experimented with materials, shapes, and sizes, finally settling on lightweight aluminum, convex, round. Then he had to decide how to paint, mount, and light them. The discs clearly show Irwin’s experiments in using the light in the room to extend the art beyond the object on to the surrounding wall.

While reading this book I had an interesting experience of synchronicity. Looking for an art outing, I checked out what was being exhibited at the Albright-Knox Gallery in Buffalo, New York (an hours drive away). Amazingly, there was an interactive multi-artist exhibit called The Art of the Senses, with similar work to Irwin’s and including James Turrell, who once worked with Irwin. At the same time, I’d googled where I could experience Irwin’s work, which is not easy to find. While at the exhibit, which was wonderful and stimulating, I came across one of Robert Irwin’s discs. It hadn’t been advertised as part of the exhibit because it’s part of their permanent collection.

“You work and work and work at something that then happens of its own accord. It wouldn’t have happened without the work, but the result is not the product of the work. There is all that preparation for receptivity – then there is something beyond – which is free. The discs were full of grace.”

In a retrospective at the Whitney Museum in New York (1977), Irwin put it this way.

“From about 1960 to 1970, I used my painting as a step-by-step process, each new series of works acting in direct response to those questions raised by the previous series. I first questioned the mark (the image) as meaning and then even as focus. I then questioned the frame as containment, the edge as the beginning and end of what I see. In this way I slowly dismantled the act of painting to consider the possibility that no-thing really transcends its immediate environment.”

This last question caused him to give up painting altogether. In 1970, he decided to give up his studio and to go “anywhere, anytime, in response.” In other words, he had nothing to do. He lived in a state of openness and let his perception wander.

Light and Space

Now that Irwin had moved beyond the frame, he now began to question the whole idea of looking “at” something.

“How might it be possible to make an art of the incidental, the peripheral, the transitory – an art of things not looked at (indeed, invisible) when looked at directly, yet still somehow perceived?”

He wondered how he could use light and sound and other kinds of energy. And, he was curious about why we separate things, i.e. an object rather than the light which reveals it. He asked himself,

“What takes place between and around things? There is no real separation line, only an intellectual one, between the object and its time environment. Nothing can exist independent of all the other things in the world.”

Here’s an example at the Museum of Contemporary Art in San Diego.

Site-Generated Installations

Irwin gradually added the elements back in through his site installations. It’s not that he thought these tools didn’t have value, but he wanted to see the canvas as one field; to give ‘ground’ (or space) it’s due. We often think of ground or space as a place within which objects lie. Irwin started looking at space, and seeing the energy within that space.

“He realized that imagery (or representation), presented a second order of reality, while he was after a first order of presence (an energy field).”

At this point, Irwin began to work with spaces themselves. Instead of forcing his ideas on to a space, he let the space speak to him. This is the ultimate in receptivity.

“When you set out to make an object, you make this new thing from scratch, whereas I was now interested in the nature of things as they already are. Given any new site, I respond to it, modulate its presence; but first I had to be invited in.”

Irwin had now arrived at his two life themes – the experience of presence and awareness of perception.

Everything since revolves around those themes. He began to study perception through the thoughts of philosophers from the past. And, he saw how perception (how we see) is the basis for all art, as well as life. His work, which includes the garden at the Getty Museum, became site-generated, meaning that the site itself dictated the possibilities of response. He began to re-introduce all of the elements, even objects, that he’d previously deleted.

The Yoga Studio

Irwin did not renounce art as object, as much as he increased awareness of the entire field. He engages the whole world and makes people a little more aware than they were the day before of the subtle beauty around them.

“That the light strikes a certain wall at a particular time of day in a particular way and it’s beautiful – that, as far as I’m concerned, now fits all my criteria for art. Aesthetic perception itself is the pure subject of art. Art existed not in objects but in a way of seeing.”

The Role of Photography

For years, Irwin would not let people photograph his work because he didn’t see how you could photograph the experience of being there. Because of this, examples of his work are limited. In more recent years, he’s relented somewhat and allowed certain photographers to document his work. One is Joel Meyerowitz, who had to consider this question – How do you photograph light, space, atmosphere, hue, texture, stillness and moment?

This is something I ask myself too and why I’m mesmerized by the photographic work of Uta Barth. For awhile now, I’ve wanted to photograph the space in the yoga studio, where I go once a week. It’s wonderfully calm and meditative with beautiful morning light and simplicity. I asked the owner if I could come in when the studio was empty and she graciously agreed. Here is one of the images.

In one of Irwin’s installations – Dia: Beacon in New York State, the effect of the space drenched in light is described as “a bathing evenness, isometric tranquility, abandonment of all hierarchies, a lulling calm, paradoxically stimulating a heightened awareness.”

This book is one fascinating and illuminating read. Weschler ends by alluding to the far-reaching possibilities of this type of work – making people aware of their perceptions – for not only art but everyday life. When we start to see differently, it changes us. When we are changed by the way we see (our mental organization), this can eventually lead to changes in our social, political, and cultural organizations. He says that revolutions don’t create change, rather, change creates revolution. Now, that’s powerful.

Fascinating post, especially since I, too, visited this exhibition at the Albright-Knox. I was enchanted by Irwin’s piece and took several photos of it. I didn’t know anything about him, thought, until I read this post! Thanks.

Always interesting to come here, Kim, and read about what you have to say and follow mind opening links and ideas! I love your last image of the window and shadow reflections.